Headline:

The Energiewende in 2014

With 2014 now firmly behind us, it is a good time to take stock of what last year meant for the Energiewende and identify the key issues that will shape 2015. Was 2014 a good year for Germany’s ambitious energy transition strategy? What positive results did it bring and what were the more worrying ones?

The Energiewende is a comprehensive programme aimed at transitioning Germany to a more sustainable energy system with drastically reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but also enhanced security of supply and economic efficiency. The key pillars of this policy are the development of renewable energy sources (RES) like wind and solar, a decrease in consumption through greater energy efficiency, the phasing out of nuclear power (set to be completed by 2022) and the progressive crowding out of fossil fuels.

In the last decade, the Energiewende has experienced significant successes, such as the rapid take-off of renewables, but it has also encountered obstacles and drawn criticism, for instance regarding high household electricity prices and the slower-than-hoped-for decline in GHG emissions.

For many of these issues, 2014 will be remembered as the year that saw confirmation of positive trends and promising signs that some hindrances can be overcome. However, other aspects continue to be at best partially addressed and might become increasingly burdensome in the coming years.

The power sector gets greener

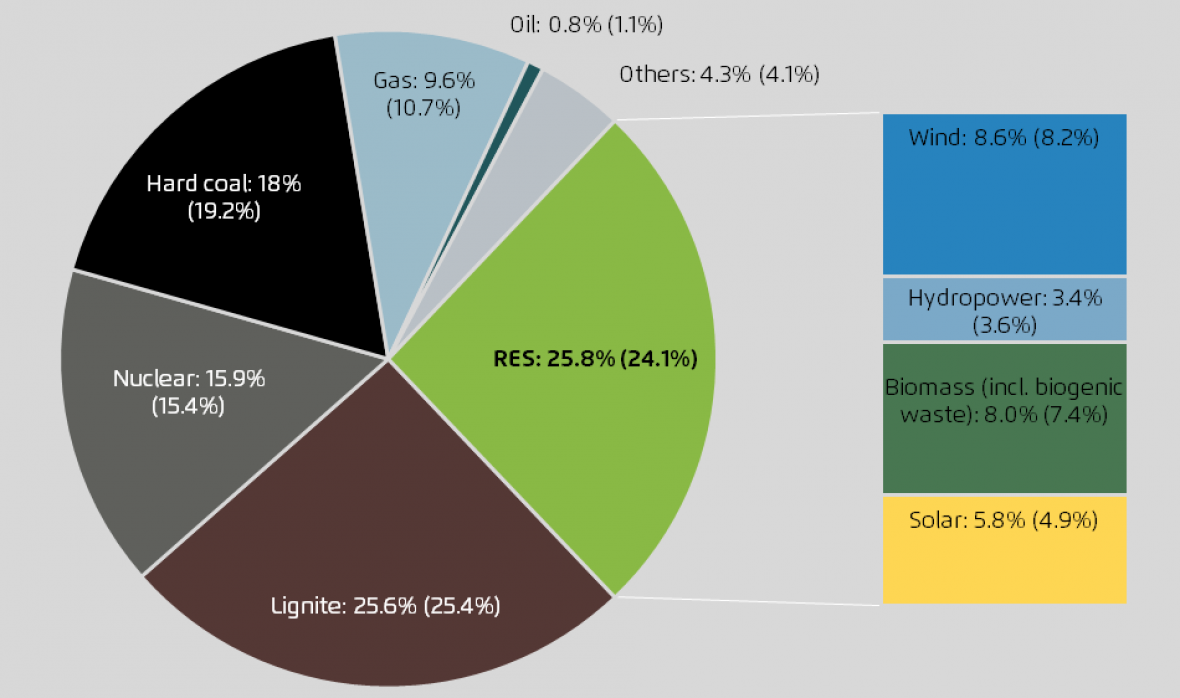

The first good news from 2014 is the continued increase in the share of RES in the power sector, which now accounts for 25.8% of gross electricity production. The growth in wind power, photovoltaic (PV) and biomass matches expectations and, if it continues, it is very likely that the 2020 target (40% of RES) will be met.

Conversely, the contribution of fossil fuels to power generation continues to decrease. In 2014, electricity production from hard coal reached its second-lowest level since 1990 (the lowest being in 2009, which was a statistical outlier due to the impact of the economic crisis). Gas consumption in the power sector continued to fall, as it has been doing since 2011. Unfortunately however, lignite (brown coal) use remains high, a trend that has not been reversed in the last decade. Nuclear power remained constant in 2014, as no plants were due to be shut down.

The electric grid remains stable, household prices might decline

One concern that is often raised is related to the risk that the growth in RES power generation will not offset the phasing out of nuclear plants, leading to insufficient supply or an increased reliance on coal to fill the gap. This would be compounded by the fact that electricity production from wind and PV is naturally intermittent, and therefore high shares of these RES could compromise grid reliability.

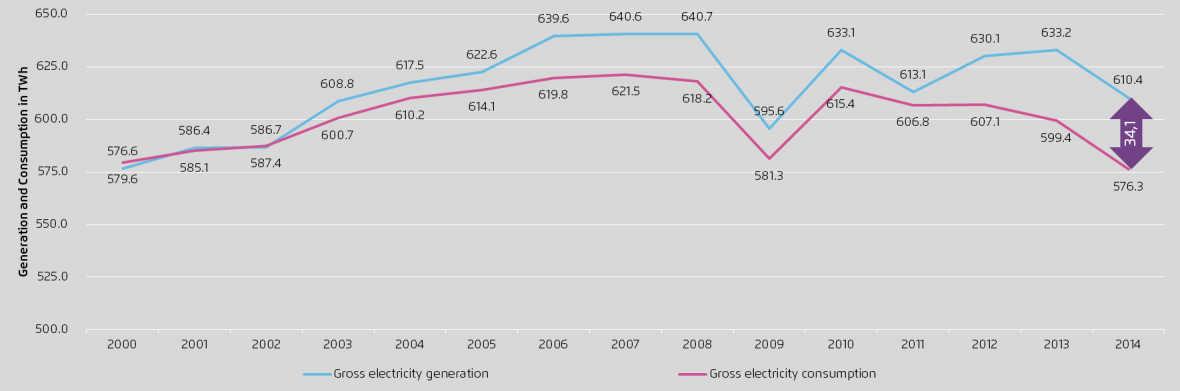

The data from 2014 tells a more optimistic story: the stability of the German grid is actually increasing, with a very low rate of power interruptions. Furthermore, the overall power supply is far from experiencing shortfalls: in 2014, Germany again generated more electricity than it needed, resulting in 34 TWh worth of net exports. Accordingly, the downward trend in the wholesale price for power that began in 2008 continues, with an average price of below EUR 40/MWh in 2014.

As for household electricity prices, which have been on the rise over the past decade, 2014 marked a slowdown, and experts predict a slight decline in 2015.

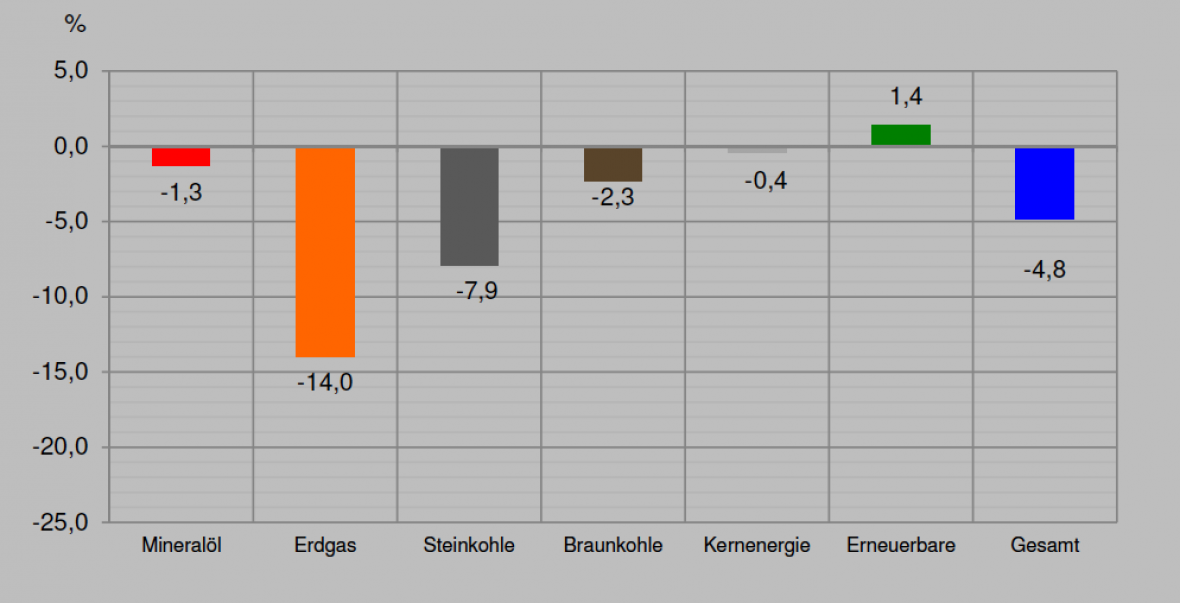

Decreasing energy consumption

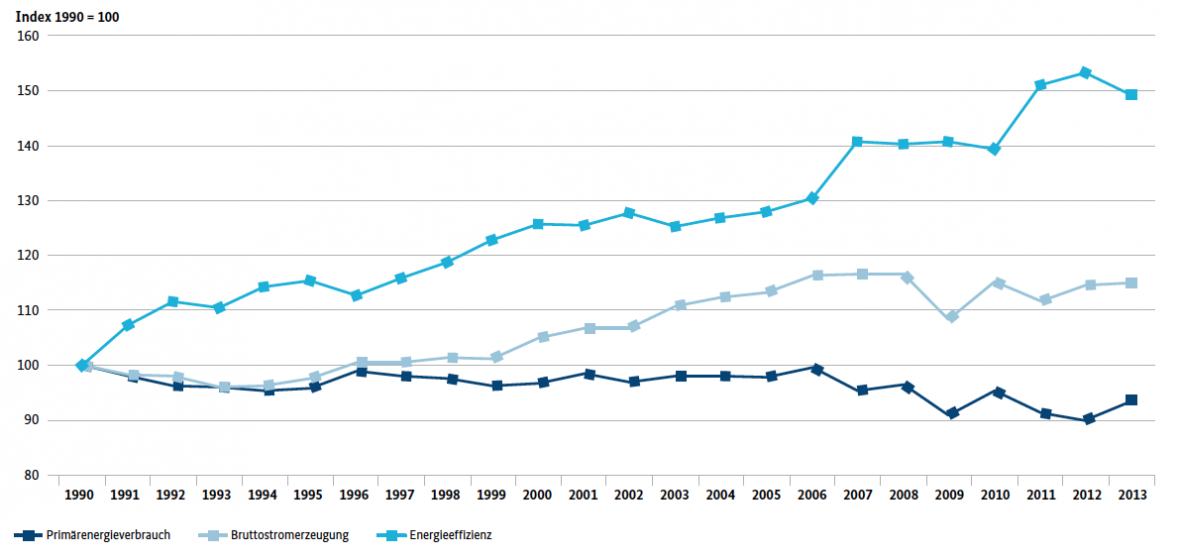

Last year was also noteworthy for the almost 5% decrease in primary energy consumption (across all sectors, including transport). While this can at least partly be attributed to the mild winter, which affected heating-related energy needs, it also exemplifies a more structural trend: since the mid-2000s, Germany’s energy consumption has stabilised or is even declining, and this despite the steady growth of GDP.

This means essentially that the impact of GDP growth on energy consumption has been mitigated, and that energy efficiency measures are proving effective. This is a positive signal for future progress in this area.

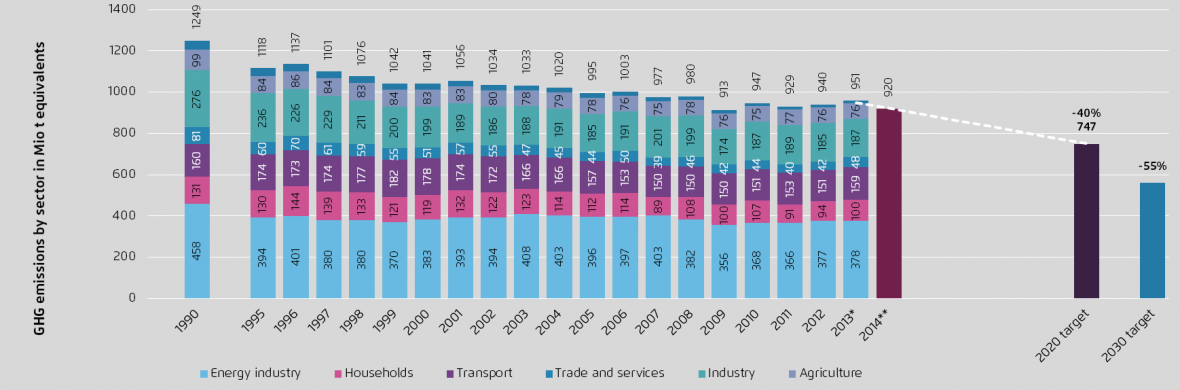

The result: GHG emissions finally on the decline

The main news for 2014: the combination of the increase in renewable electricity production and the overall decrease in energy use have led to a very welcome dip in GHG emissions. Total energy-related emissions (which constitute more than 90% of all emissions) are estimated to have decreased by ~30 Mt CO2-equivalent; in the power sector, CO2 emissions were cut by 5%. This result has a practical and symbolic significance: it shows that the Energiewende is finally ‘paying off’ in terms of emissions reduction, and it increases the likelihood that the 2020 target will be achieved at a moment when doubts were surfacing.

Looking forward: what challenges does the Energiewende face?

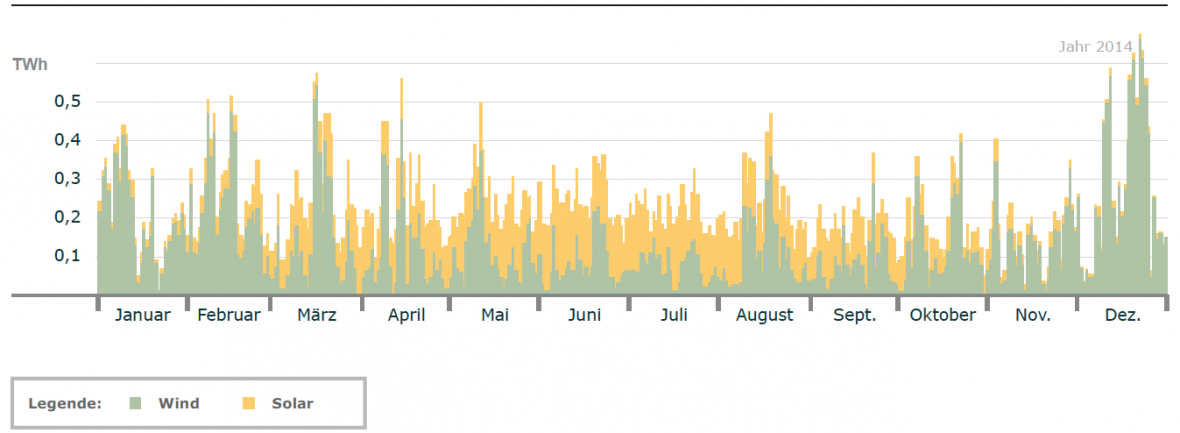

In 2015, the share of wind and solar in the power mix will increase further, making it even more important to analyse how the system should be shaped to best integrate growing amounts of intermittent renewable electricity. The fact that, on an annual average, Germany has no shortage of power supply should not conceal the significant variations that occur on a day-to-day (and sometimes hour-per-hour) basis:

There are days when renewable power generation is very low and demand is mostly met by conventional plants, and others when it can surge to reach three quarters of demand. These peaks also contribute to negative power prices, something that happened for a total of 64 hours in 2014. Low or negative prices reduce the economic viability of maintaining backup generation capacity (especially in the form of conventional plants), which is something that Germany still requires. And even in a long-term scenario where renewables will make up more than 90% of electricity consumption, there will still be a need for dispatchable power generation to satisfy peak load demand.

The debate on how to address this issue will undoubtedly gain relevance in 2015. Proposed solutions include the establishment of a capacity market, while other approaches aim to offset RES intermittency by converting electricity into fuels (power-to-gas, power-to-liquid).

Last summer, the parliament adopted a slate of amendments to the Renewable Energy Sources Act, which introduce, among other things, updated targets for renewables deployment, flexible feed-in tariffs and market premium mechanisms, with a focus on containing costs. Some provisions have given rise to criticisms, and it will be important to monitor the impact of this reform on the power sector, especially in the light of the planned transition from feed-in-tariffs to competitive bidding (which in the case of PV will already begin in April 2015).

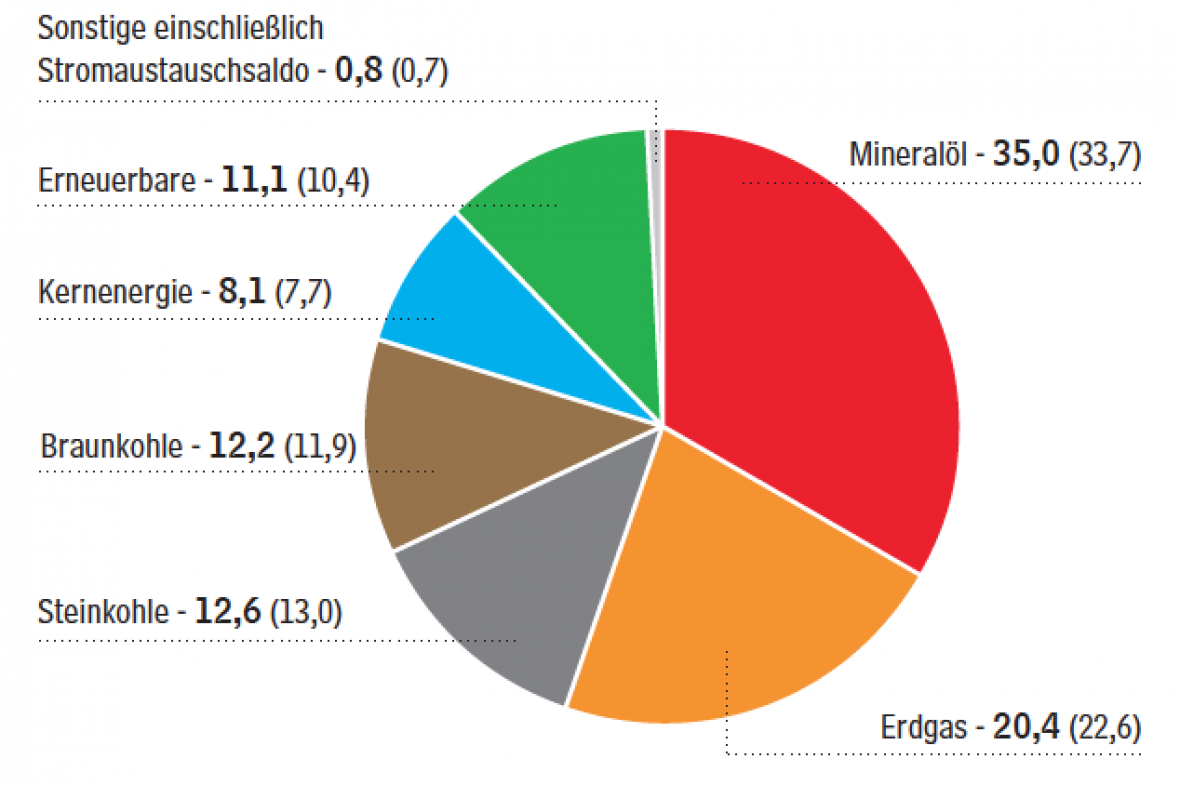

In any case, the good performance of renewables in the power sector should not mask the bigger picture: electricity only accounts for one fifth of Germany’s total energy consumption (and roughly 40% of its GHG emissions), while other energy needs, such as transport and non-electric heating, are still predominantly supplied by fossil fuels.

The chart shows that when we take this broader view, the share of renewables drops to 11.1%, a level that has not increased significantly in the last 5 years. Moreover, biomass makes up the lion’s share of this figure; solar and wind power together only represent less than 3% of Germany’s energy consumption.

Continued efforts to make the power sector greener will directly translate into lower emissions, and perhaps suffice to achieve the 2020 targets. But what about the next milestones? More specifically, how can we address the use of fossil fuels in the heating and transport sectors? Leaving cross-cutting energy efficiency measures to one side, this is currently a largely open question. Heating systems for residential buildings still rely mainly on fossil fuels, and in 2014 more than half of all newly constructed apartments were equipped with natural gas heating. As for transportation, out of Germany’s 44 million vehicles there are only 24 000 electric cars – far from the government’s goal of reaching 1 million plug-in vehicles by 2020.

The climate package put forward by the government last December contains some measures in this respect as part of a wider effort aimed at accelerating GHG emissions reduction in the run-up to 2020. Whether they prove successful in 2015 and the coming years will be key to ensuring that the Energiewende stays on track.

Photo: istock/vschlichting

Add new comment