Anti-extractivist Art: Responding to the Unequal Geographies of Climate Breakdown

21.11.2025

As COP30 unfolds in Belém—the first time the UN climate summit has been held in the Amazon—the contradictions of our planetary emergency are painfully apparent. Nowhere is this clearer than in Vazios sobre Terra: co-criar como rota de fuga (Absent Matters: Co-creating as an emergency exit), an exhibition that gathers more than forty artists and collectives from Brazil, Ghana, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Kenya, Germany, Pakistan, India, Iran, Turkey, and the Netherlands. Installed at the Museu de Arte de Belém (MABE) and the Entertainment + Culture Pavilion at the Blue Zone, the exhibition asks a deceptively simple question: “How can we return to the earth and to one another?”

The curators, Elsa Cuissard and Isadora Canela, have assembled a transcontinental constellation of works that make visible the global geography of extractivism—something that is often treated as a technical issue of “resource management,” but is in fact the underlying political economy of the climate crisis itself. The exhibition maps extraction as a global structure of unequal exchange, featuring works ranging from Bárbara Marcel’s Golden Tone (a video installation tracing the development and export of mining technologies from Harz, Germany) to a textile collage by the Web & Stopmines Collective highlighting the catastrophic scale of contemporary mining, and Paula Sampaio’s photographic works documenting life in communities along a railway operated by Vale mining corporation in northern Brazil.

The show’s geography encompasses regions most affected by ecological devastation—including the Amazon, South Asia, Southern Africa, and the Middle East—underscoring that the climate crisis is fundamentally a material and historical crisis rooted in centuries-long circuits of colonial dispossession. As countries with minimal historical emissions—across Africa, South Asia, and the Amazon—face the sharpest edges of climate disaster, the exhibition brings Jason Hickel’s blunt assessment into focus:

“The Global North is responsible for 92 percent of emissions in excess of the planetary boundary, while the consequences of climate breakdown fall disproportionately upon the global South […] economic growth in the North relies on patterns of colonization: the appropriation of atmospheric commons, and the appropriation of Southern resources and labour.”

Thea Riofrancos argues that the extraction of raw materials in one region and their processing into clean energy technologies consumed elsewhere replicates historical patterns of exploitation and perpetuates historically colonial relationships, reinforcing the peripheral position of resource-rich nations within the global economic system and integrating them into capitalism through the development of mining industries located far from centres of finance and industry. That profound inversion—those who contributed least suffering first and worst—is the very definition of climate injustice.

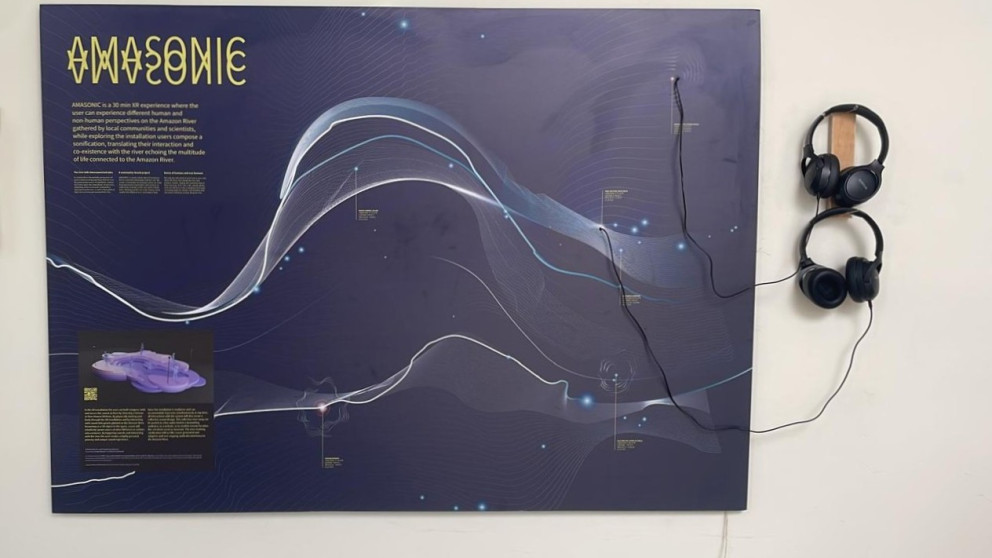

Amid this global conversation, one of the exhibition’s most quietly powerful presences is Dr Maria Cecília Oliveira (RIFS Research Group Leader for “Ecopolitics and Just Transformations”), who created Amasonic, an immersive sound project that rejects both the exoticization of the Amazon and the extractive logic of technological ‘fieldwork’. Amasonic was co-created with Marcel van Brakel, founder of the interdisciplinary Dutch experience design collective Polymorf, and produced by Studio Biarritz and Polymorf, with the participation of local communities and bio-acoustic specialist Jorge Menezes and anthropologist Patricia Carvalho Rosa. The work shown here is a proof of concept and is currently under discussion with communities and scientists in the region. The piece was also selected for the DOC LAB Forum at the IDFA International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam, and is now seeking partners and collaborators for production and distribution in 2026/27.

Originally from the periphery of São Paulo and now living in Berlin, Oliveira approaches art not as representation but as a practice—a way of expanding political imaginations and creating small ruptures in narratives that portray the Amazon as a distant, spectacular nature-scape. During the exhibition’s roundtable, she emphasized the need to break from the visual tropes that dominate European imaginaries of the forest. Rather than repeating the “green spectacle,” Amasonic listens to the Amazon through water, plants, and fish—capturing the acoustic life worlds often overlooked by Western science.

The project evolved from a visit to the Mamirauá Institute in Tefé, which uses bioacoustic technologies to monitor forest animals. Oliveira and her collaborators were spurred to change the underlying logic: instead of extracting data to be processed in faraway labs, they sought to build an acoustic practice that stays in the Amazon, shared and co-developed with local communities who already possess generations of expertise in listening. Fishermen who read a river by sound, communities who know bird movements and tidal rhythms—these are, as she puts it, “the people who already hold the technology.”

Unlike many externally funded projects, which arrive with specialists and depart with equipment (and data), Amasonic is committed to leaving both knowledge and technology within the community. It envisions a five-year collaborative programme in which ribeirinho (riverside) researchers, community members, and academics co-create a living archive of underwater and riverside sound—an epistemology rooted in reciprocity, not extraction.

Crucially, Amasonic is relational: it rejects the isolating experience of VR headsets and instead creates shared sensory experiences in collective space. In a COP dominated by metrics, carbon budgets, and financial pledges, Oliveira calls for something radically different: a research practice rooted in the lived and messy reality of rivers that are threatened by hydroelectric development, communities and landscapes affected by the Ferrogrão railway and the reactivation of BR-319 highway, fluvial corridors for commodity exports, and the growing pressure on Amazonian waterways.

As Oliveira notes, this COP has been shaped by the voices of women like Audicélia (Cipoal) and Alessandra Munduruku, who confront the extractivist ‘common sense’ of development with uncompromising clarity. Oliveira positions her anti-extractivist work alongside theirs—an insistence that art and research can serve as counter-lucidity, a refusal of the developmental gaze that sees the Amazon only as logistics, energy corridors, and mineral deposits.

What Vazios sobre Terra ultimately offers is not a catalogue of harms but a political grammar: a way of understanding extractivism not as a sector but as a colonial relation that spans continents. Its geography mirrors the asymmetry Hickel describes. Exporters of raw materials; importers of biodiversity threats. Territories hollowed out; supply chains that enrich others.

The exhibition forces the world to confront a central truth of COP30: the Amazon is not merely a site of emissions or mitigation, but a frontline of colonial extraction with global consequences. The empty spaces in the exhibition’s title—vazios—are not voids but wounds. The works gathered here insist that any future worth imagining demands not technological escape, but the restoration of reciprocal relations with land, water, and one another. Oliveira’s contribution is emblematic of this shift: to listen with the Amazon, not to it. To create knowledge that circulates laterally rather than flowing Northward, and to practice research that leaves behind more than just datasets. As COP30 negotiators debate emissions curves inside the plenary halls, Vazios sobre Terra reminds us that the climate crisis is not only about carbon. It is about extraction, exchange, and the unequal geography of survival.

And it asks, with a sense of urgency: How might we return to the earth—and to each other—before the void expands further?