The Diesel Boom and the Climate: Study Lends More Weight to Calls to End Subsidies

07.11.2018

Nitrogen oxides have dominated the diesel emissions scandal. But what about carbon dioxide emissions? For a long time, diesel engines were considered indispensable for efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, and this is one of the reasons for the privileged treatment of diesel fuel within the tax systems of many European countries, including Germany. This cost advantage has caused the number of newly registered diesel cars to sky-rocket over the last twenty years. Scientists have now calculated the exact effects of this “diesel boom”: In a new study published in the journal “Atmospheric Environment” they show that the diesel boom in Europe has failed to benefit the climate.

In previous studies, carbon dioxide emissions were calculated on the basis of official emission factors, rather than the significantly higher real-world emission values. Data collected by the International Council on Clean Transportation show that the difference between real-world and type-approval fuel consumption has grown in recent years. According to the data, in 2015 the real-world consumption of new passenger cars was on average 42 percent higher.

The researchers Eckard Helmers (Trier University of Applied Sciences), Joana Leitão (IASS), Uwe Tietge (International Council on Clean Transportation) and Tim Butler (IASS) modelled three different scenarios for the study in order to assess the climate impacts of diesel subsidies in the 15 states that have belonged to the European Union since 1995 and which account for most of the European car market. The first scenario tracks developments in the historical vehicle market: Between 1995 and 2015 the overall share of newly registered diesel cars climbed across the EU-15 from 22.6 percent to 52.1 percent. In the second scenario, the researchers assumed that the share of diesel cars would have remained constant at 22.6 percent in the absence of relevant subsidies. In the third scenario, they calculated how the vehicle inventory and emissions would have developed if the EU had followed the Japanese precedent of promoting hybrid cars and, additionally, natural gas vehicles. Under this scenario, the share of diesel vehicles would have fallen to 11.6 percent by 2015, while that of hybrid and natural gas vehicles would have risen to 39 and 4 percent, respectively.

The emissions, calculated in carbon dioxide equivalents, are almost identical in the real-world scenario and in the scenario in which it is assumed that the share of diesel cars remains constant. In the third scenario, in which the share of hybrid and natural gas vehicles grows over time, carbon dioxide emissions are 3.4 percent lower than those seen in the first scenario. “It was particularly interesting to see that the total emissions of all newly registered passenger vehicles have actually increased slightly in recent years despite the growing number of low-emission vehicles being registered. This would appear to be due to the simple fact that more cars were registered in this period,” explains Tim Butler. In other words, while individual vehicles are emitting less carbon dioxide, the increase in the total number of cars on the road means that technological improvements have not significantly reduced the total emissions of diesel passenger vehicles.

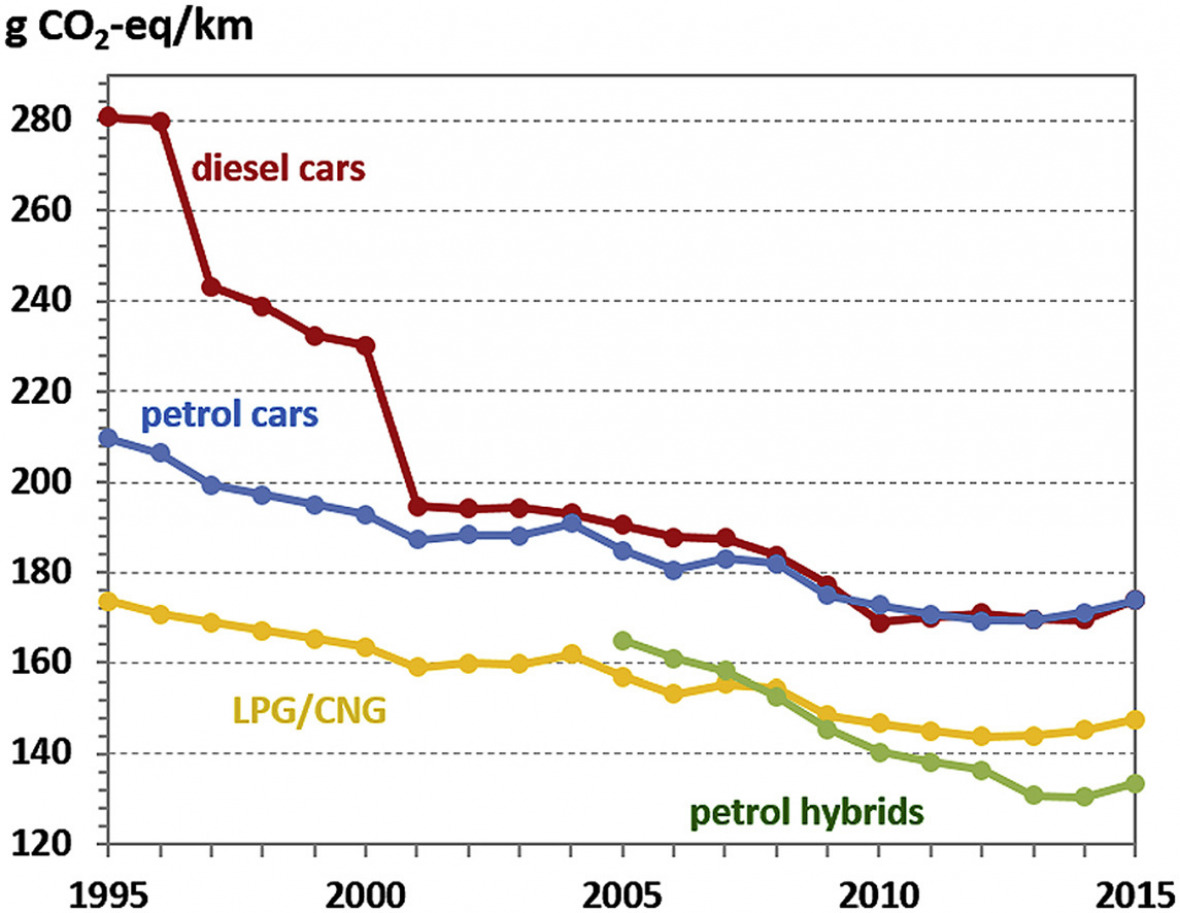

According to Joana Leitão, the study is further proof that the privileged treatment of diesel fuel under German tax and fiscal law is unjustified from an environmental policy perspective. Carbon dioxide emissions from diesel and gasoline engines have not differed significantly since 2001, thus dispelling the long-standing myth that diesel vehicles are somehow a “climate friendly” alternative. “In the 1990s and early 2000s, the promotion of fuel-efficient diesel vehicles led to a modest reduction in carbon dioxide emissions; however, this was paralleled by an increase in particulate emissions, as the large majority of diesel vehicles were not equipped with particulate filters at this time. Particulate matter, or soot, is a well known air pollutant, but it is also a climate forcer. These soot emissions cancel out the positive climate effect of the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions,” explains Leitão. Today, all diesel passenger cars are equipped with particulate filters, however there is no guarantee that these vehicles will be operated with functioning filters throughout their entire vehicle life.

A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions can only be achieved by reducing either the total vehicle inventory or its real-world emission levels. In order to achieve the latter, policymakers must introduce stricter carbon dioxide standards and monitor their compliance; in addition to this, measures are needed to increase the share of low-emission vehicles.

- Eckard Helmers, Joana Leitão, Uwe Tietge, Tim Butler, CO2-equivalent emissions from European passenger vehicles in the years 1995–2015 based on real-world use: Assessing the climate benefit of the European “diesel boom”, Atmospheric Environment, Volume 198, 2019, Pages 122-132, ISSN 1352-2310.