Headline:

Energy Transition in France: Following in Germany’s Footsteps?

Recently, the Eiffel Tower in Paris was equipped with two small vertical wind turbines, which, while they spawned many news articles, have a generation capacity that is rather symbolic. In the same week, the French Parliament debated and voted on an extensive new bill laying out the country’s plans for transforming its energy supply and curbing GHG emissions. Is France on its way to an energy transition?

The Bill on the Energy Transition for Green Growth (PDF in French) covers areas ranging from renewables development to waste management and cleaner transportation, and sets strategic objectives for the next decades. It was adopted last autumn by the National Assembly. However, following substantive amendments by the Senate in March 2015, the text will now undergo further readings by both chambers in a legislative process that should be finalised in two to three months.

This is not the first time that a French Government has sought to implement measures to promote a greener energy sector: since the early 2000s, various laws have been adopted with this in mind, for instance, setting up support schemes for renewables. Yet they were mostly sector-specific and lacked a unified approach and goals. This new legislation is meant to finally provide a comprehensive framework and strategic drive for France’s energy transition: in its scope and ambition, it is comparable to Germany’s Energiewende. And indeed, the comparison with the German situation is useful for shedding more light on French energy policy in the past and the present.

France’s transition énergétique shares many goals and policies of Germany’s Energiewende

At first glance, the two countries share many characteristics: they are both modern, industrialised nations, with economies and populations of a similar size and a diversified energy sector; on average, German citizens consume just as much energy per year as their French neighbours. The total electricity production of each country is also comparable.

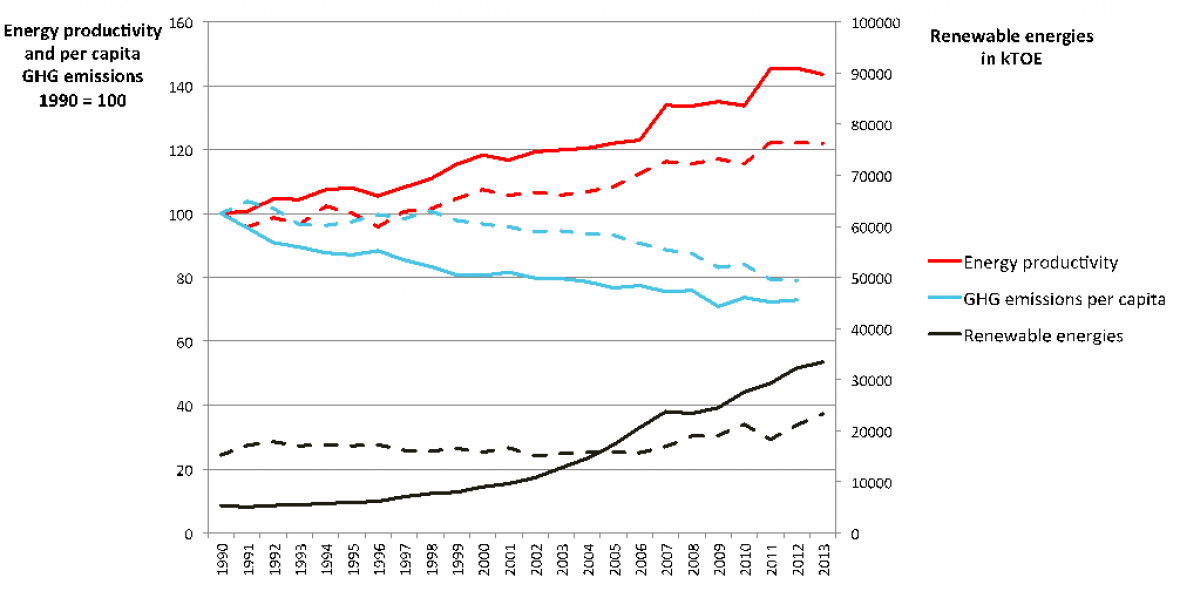

More importantly, both France and Germany have committed themselves to making their energy system cleaner and more efficient, with increasingly tangible results in the last decade (Figure 1). Nonetheless, when it comes to policy choices and long-term trajectories, France and Germany are often presented as following two distinctive, or even competing, pathways to the energy transition.

In France especially, the German Energiewende is most often portrayed either as a model to emulate or a failure to avoid, but always as something fundamentally different from France’s approach.

Yet a closer look at the two countries’ energy policies, particularly in the light of this new French law, reveals how much their two energy transition strategies actually have in common.

The French targets for GHG reduction, renewables development and energy use (table) are broadly in line with those set by Germany: though less ambitious in the case of the 2020 milestone, they aim to match or even outdo Germany by 2030 and 2050. For instance, the halving of total energy consumption by 2050 is a shared objective: an ambitious endeavour to be achieved mainly through cross-sector energy efficiency measures.

Even in the case of nuclear power, which is often singled out as the main point of difference between the two countries, the strategies are in a way comparable. France aims at bringing the share of nuclear power in the electricity mix down from its current 75% to 50% by 2025: in terms of power generation and the number of plants that will have to be closed, this is very much equivalent to the nuclear phase-out Germany is carrying out over a similar time frame (2011–2022).

Another shared feature, at the core of each country’s strategy, is the promotion

of renewable energy sources (RES) development. Like Germany, France has been establishing various support schemes for RES since the early 2000s, from subsidies to tax breaks and special tenders, including, of course, feed-in tariffs for renewable electricity. This new law intends to revise and expand these mechanisms. The modifications are in many ways akin to the German Government’s revision of the Renewable Energies Act (EEG) last summer, particularly since they too aim at complying with EU directives on increased market integration for renewables – which entail, among other things, the transition from fixed feed-in tariffs to flexible market premiums.

In short, Germany and France are hardly on completely different paths, at least as far as political goals go. The real differences between the two might rather stem from the fact that in France, despite these efforts, the energy transition is in some respects still lagging behind.

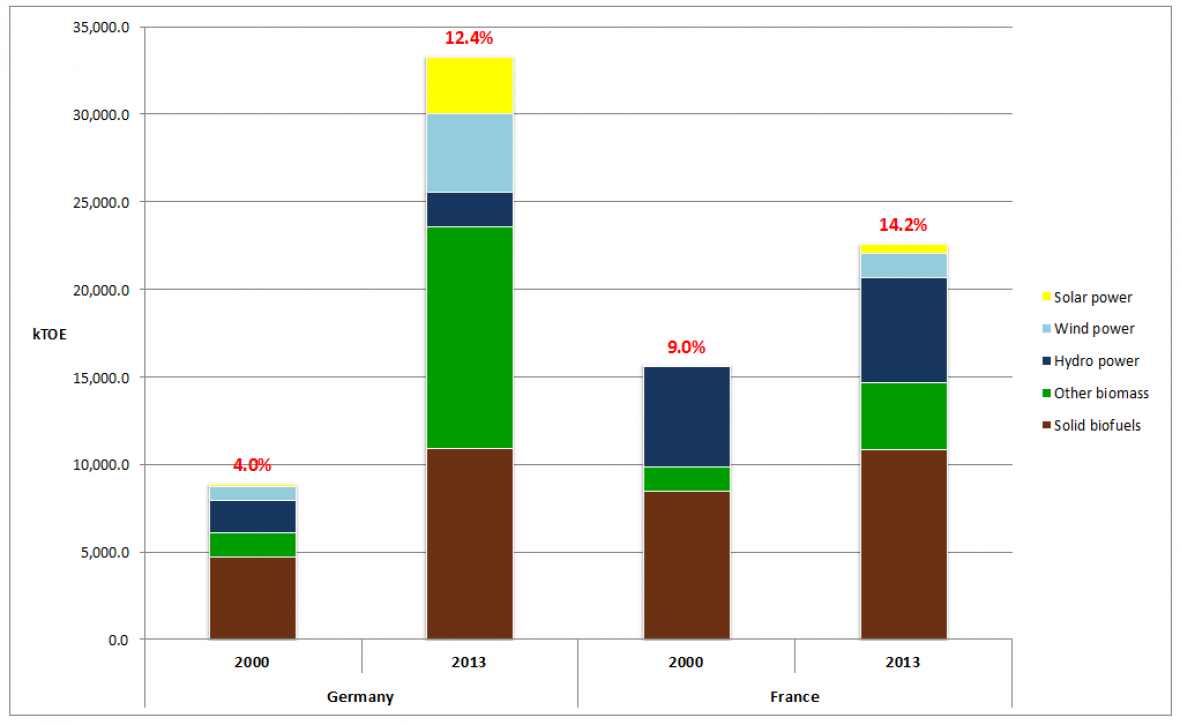

France’s energy mix and the slow development of renewables

In Germany, the rapid development of renewable energies, especially solar and wind, in the last five to ten years has surpassed even the more optimistic forecasts. Overall, RES production has increased almost sevenfold since 1990. In France, the situation is different: historically, renewable energies have long accounted for a larger share of the energy mix, thanks mainly to the contributions of hydropower and solid biofuels like firewood. Annual consumption of the latter, for instance, varies between 8 and 10 Mtoe per year, a figure that has essentially not changed since 1970 (report in French). In the case of hydropower, the possibilities for additional increases have almost been exhausted. Hence, further growth in renewables is expected to come from biofuels, other types of biomass, and, of course, wind and solar power – for both of which France has a high natural potential.

However, despite the various incentives, the hoped-for take off in this area has at least partly failed to materialise (Figure 2). In 2014, installed capacity of solar and onshore wind totalled 5.3 and 9.2 GW respectively, as opposed to Germany’s 38 and 36 GW. And there is still no offshore wind capacity in France (although at least 3 000 MW are due to be installed by 2020).

As part of the EU’s 2020 climate and energy package, France would have to raise its share of renewables in final energy consumption from the current 14% to 23%, a goal that is unlikely to be met given recent trends. Of course, many hope that the new law will revive the impetus for RES development, for instance through measures that simplify administration and thereby cut approval times for RES projects. But time is running out, and many issues still need to be clarified: from the minimum distance between wind farms and residential housing, a topic that has been passed back and forth between the two chambers of Parliament, to the hitherto unknown specifics of the new RES support schemes, which will have to be determined in implementation decrees after the law is passed.

Finally, and beyond the 2020 targets, it is also unclear whether this law will be able to address the structural factors that have so far inhibited RES development in France – and chief amongst them is the issue of nuclear power.

What’s the future of nuclear power in France?

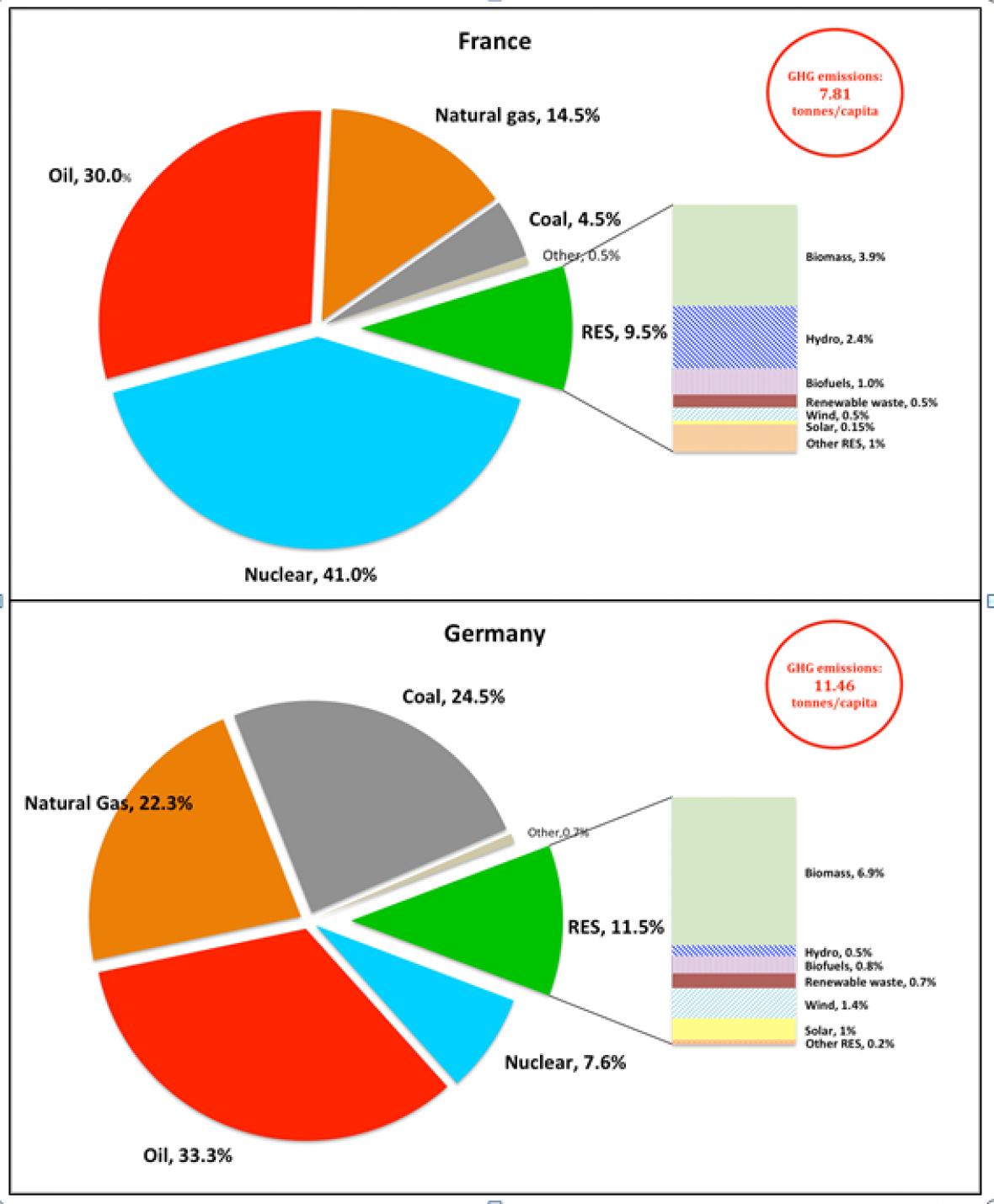

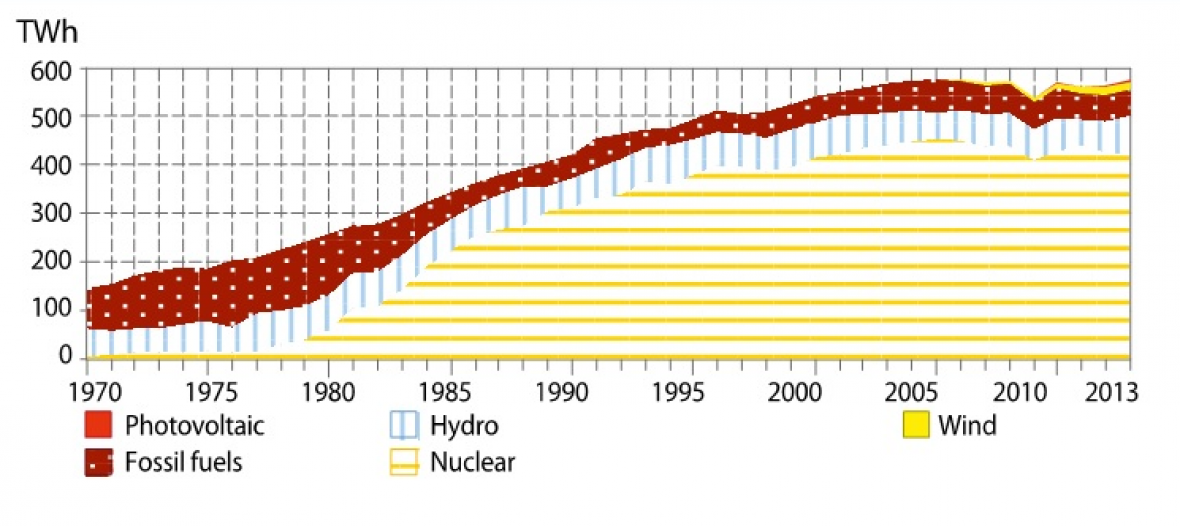

France’s history of nuclear power is a long one, but the real beginning of the ‘all-nuclear’ programme can be traced back to the oil crisis of 1973. In the two decades after that, the share of nuclear power rose from almost zero to three quarters of the electricity mix and 40% of primary energy consumption (Figure 4). In the process, many oil- and coal-fired power plants were crowded out. Today, the country has 59 nuclear plants, which supply more than 400 TWh per year – a far higher amount than wind and solar combined (23 TWh in 2014).

For many analysts, the prevalence of nuclear power in France’s energy mix is one of the main reasons why renewables are not taking off as fast as in Germany; France already produces more electricity than it consumes (on a yearly basis), so there is no acute need for alternative power generation solutions.

But challenging the preponderance of nuclear power is no easy task. First of all, France lacks the kind of clear-cut public rejection of nuclear power found in Germany: according to regularly conducted polls, the French population’s opinion of nuclear power has been more or less evenly split between negative and positive views for the last two decades. In a sense, the nuclear option has for a long time represented a kind of national consensus, benefiting from large cross-party political support. Today, an estimated 200 000 jobs are directly or indirectly related to a nuclear industry that is amongst the biggest in the world.

In the light of all this, the Government’s proposed decision to cut the share of nuclear power to 50% by 2025 should be understood as a truly significant political statement, reversing an all-nuclear strategy that has prevailed for more than three decades. Unfortunately, the French Senate (where opposition parties have a majority) has partially diluted this objective in a number of amendments that removed the 2025 deadline and made the reduction in nuclear power contingent on “preserving energy independence and competitive electricity prices, and on ensuring it does not lead to an increase in GHG emissions”. It remains to be seen whether the 2025 date will be reinstated in the next steps of the legislative process.

In any case, technical and economic issues are also to be taken into account when planning the timeline of any phase-out. In the next few years, many nuclear plants will reach the end of their initial 40-year lifetimes, forcing difficult and financially consequential decisions on whether to close them down or extend their commissions by a further 10 to 30 years. Recently discovered flaws in the new-generation EPR nuclear reactor that is meant to replace aging plants are further complicating the issue.

In sum, the idea of trimming down nuclear power to make room for renewables is now more or less generally accepted; but the actual time frame and the practicalities of achieving that are still largely unknown.

Democratic participation and decentralisation in the energy transition

In addition to nuclear power, the governance aspects of the energy transition are often seen to exemplify substantive differences between the two countries. Typically, and schematically, Germany is characterised as following a ‘bottom-up’ approach, while France’s energy transition is assumed to be more ‘top-down’. This also relates to public support for, and participation in, energy transformation processes.

In fact, and at least according to various opinion polls[1], the French are increasingly aware of problems related to climate change and the environment; they are in favour of renewables and willing to make efforts to reduce their energy consumption. Global warming and air pollution are at the top of their environmental concerns. But it is equally clear that these issues almost always take a back seat to more pressing concerns, namely, unemployment, purchasing power and inequalities. Accordingly, while climate change and especially energy-related subjects have slowly been gaining importance in elections and political discourse, they have hardly ever been major, vote-deciding issues.

The relatively modest role played by these topics in French democratic life is both a consequence of and a reason for the historically highly centralised governance system for energy policy. In the past, strategic energy decisions (such as the all-nuclear programme) have tended to be enacted by the executive branch alone, without parliamentary debate or oversight, while local governing bodies (from regions to municipalities) have always had little or no say in these matters.

Nowhere is this centralisation more visible than in the power sector: the state-owned company Électricité de France (EDF) completely dominates power generation (86% of electricity production) and retail, as well as transmission and distribution via subsidiaries. By contrast, the German power sector is significantly more competitive and decentralised, particularly with respect to renewable energy facilities, half of which are owned by private citizens. Indeed, when it comes to citizen-led energy initiatives, the difference between the two countries is startling: while there are hundreds of renewable energy cooperatives in Germany, they are almost non-existent in France.

Still, there has been something of a paradigm shift in France in recent years, brought about by the environmental agenda and the growing recognition that decentralisation and citizen participation are necessary for a successful energy transition. This is now increasingly accepted in political discourse, and has led to various reforms, but nothing approaching radical change yet.

The new law aspires to go further in this direction with a number of measures. Regions are being given greater competences for implementing their own energy-related plans (especially concerning energy efficiency), while municipalities will be allowed to invest in commercial RES projects. Citizen involvement and energy cooperatives are also being promoted. It is hard to tell whether this will be enough to break up monopolies and empower local communities. More generally, it is perhaps too early to pass judgement on the successes and failures of the French energy transition. In a sense, France is only now establishing the kind of legislative framework and political consensus that Germany achieved a few years ago. The international context is also particularly relevant: Paris will host the 21st UN Climate Change Conference at the end of the year. France’s hopes of attaining a binding, universal agreement will be better served if the country can show the world it is doing its bit.

Header photo: shutterstock/Vaclav Volrab

[1] The Sustainable Development Ministry has published three surveys on this topic (in French only), available here, here and here.

Add new comment